Sant Just Desvern, a small satellite town on the southwestern outskirts of Barcelona, is a place of industry. Huge warehouses with corrugated roofs line the leafy streets. Most are owned by companies producing perfume, machinery or electrical equipment, with one notable exception. La Nave, or "The Ship," is a vast blue building with high, panelled ceilings, split down the middle into two spaces. When I visited on a scorching day in June, the first was overflowing with hundreds of giant toys and party props, stuffed onto rows of towering shelves. The range of paraphernalia was mind-boggling, from oversized sheriff hats and discarded chicken feet to foam Funktion-Ones and yellow taxis with eyes for wheels.

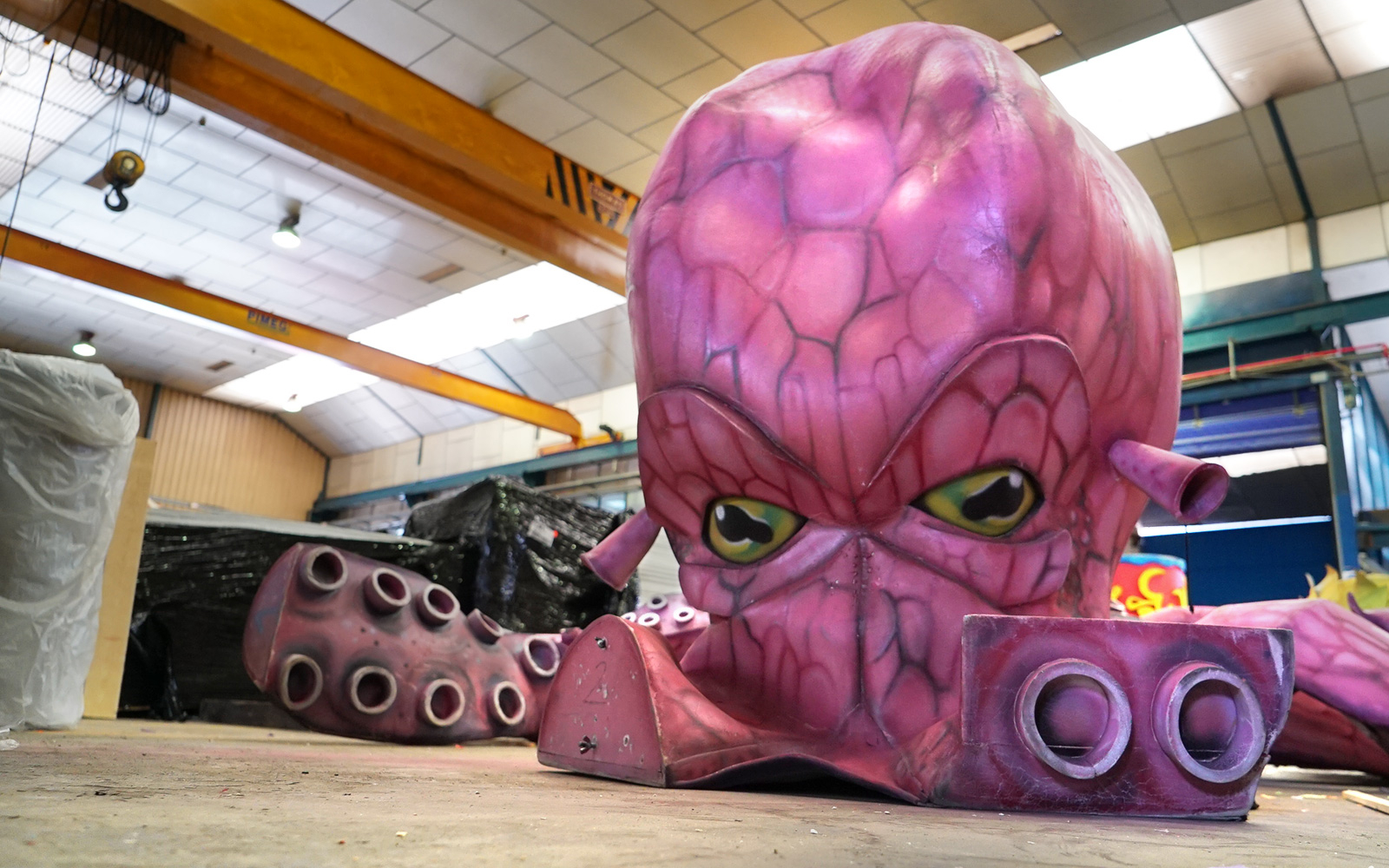

The second space was larger, brighter and more ordered. Toiling among dismantled purple octopuses and huge genie lamps were a dozen or so technicians, painters and carpenters, each of them mending or building part of a stage set. Tucked away to the right, a man operated a machine for carving wood into intricate designs. Through a door was a costume department, with rails heaving with colourful fancy dress. Upstairs, a woman grappled with a coiled plastic snake in a smaller workshop, which connected to La Nave's control room, the office of Italian-born clown and circus performer Nico Grazioso. Taped to the wall was a scruffy poster of Charlie Chaplin in full WWI garb.

La Nave is the central warehouse of Elrow, the Barcelona-based clubbing brand whose unique and theatrical approach to events is currently taking the world by storm. Launched in 2010, it's arguably the most popular party on the global circuit right now. It merges theatre, dance, puppetry and club music to create larger-than-life atmospheres that are wild, silly and extremely colourful. What started as a weekly party in Barcelona is now a global enterprise: in 2017, Elrow will host 132 events in more than 25 countries, reaching an estimated audience of 1.7 million people.

"It's the best clubbing experience you can get, hands down," said Rag Satguru, Elrow's UK partner. "Somewhere between Cream, Cirque Du Soleil, Sensation White and Manumission. They're the references."

The name of the company behind Elrow is Elrow Family, which isn't just another example of the dance music cliché. Elrow's two directors, Juan Arnau Lasierra (AKA Juanito) and Cruz Arnau Lasierra (AKA Cruz), are brother and sister—his official title is CEO, she's head of marketing and sponsorship. They're the sixth generation in their family to work in the entertainment industry, the latest in a long line of bar, ballroom and nightclub owners that stretches back to the 19th century. It's a legacy the family are proud of—on the website, beneath the Elrow Family logo, sits the company tagline: "Entertainers Since 1870."

For those in the family, Elrow represents a high point in nearly 150 years in the industry. The company currently employs 85 full-time staff, spread between offices and warehouses in Barcelona, Ibiza, New York and Shanghai. Another 50 to 400 part-time workers are contracted for every show. In addition to Elrow, the company oversees two clubs: Florida135, which celebrates its 75th anniversary in December, and the spiritual home of Elrow, Row 14, a 4,500-capacity venue just outside of Barcelona. There's also Groove Parade, AKA Monegros Festival, which until it went on indefinite hiatus in 2015, ran for 20 years as one of Spain's premier dance music events.

In February of 2017, Juanito and Cruz decided to elevate Elrow Family to the next level. They secured investment from Superstruct Entertainment, the live music division of American private equity firm Providence Equity Partners. Superstruct, formed in 2017, is headed up by James Barton, the Liverpool-born club and festival magnate behind the Creamfields franchise. It was a move that spoke to Elrow's world-conquering ambitions. Since then, they've hosted their first Asia show, in Shanghai, and events in Mumbai and Thailand are in the pipeline. There are also plans for a new office in South America.

Elrow is at the forefront of a growing trend in experiential clubbing, where the emphasis is on the production and the decoration over the music. These kinds of parties go down particularly well in the UK, with promoters like Good Life, Magic Door and Cirque Du Soul hosting flamboyant events around the country and abroad. "If you were to write it down as an equation, Elrow would be 25% music, 25% the performers, 25% the decoration and 25% the crowd," Elrow's bookings director, Victor De La Serna, told me in Barcelona. It's a formula that has widened the party's appeal well beyond the traditional clubbing community.

"Elrow is an Everyman's brand," said Satguru. "Use this quote if you want: you could take your mum to Elrow. In fact, I've taken my mum to Elrow. Because it's where theatre meets clubbing, the story is there in the nightclub, and it's giving you something that no one else can provide. No one else can build a stage set like they can, or bring performers in costumes like they can."

"Elrow has one big advantage," said Andres Campo, a resident DJ at Florida 135 who plays regularly at Elrow. "It appeals to people who simply enjoy partying in the open air and being in a lively and colourful atmosphere. The party's success is taking this whole culture of underground clubbing in dark rooms and flipping it on its head."

Juan Arnau Lasierra and Cruz Arnau Lasierra

Confetti and inflatables are the cornerstones of any Elrow party, as are the dozens of professionally trained actors and stilt walkers whose job it is to interact with the audience and create a carnival-style atmosphere. When I visited Row 14 at the end of April for one of its flagship all-dayers, pot-bellied drag queens with smeared lipstick and balloons for breasts thrust plates of paella into people's hands as they walked in. A team of 40 actors and 16 stilt-walkers were working that day, roaming the club in 15-minute shifts. Some worked alone, others in twos or threes, improvising and feeding off the crowd. I followed a man with an oversized nose dressed as the Pope as he blessed everyone in his path with "holy" water.

London-based infrastructure architect Rene Ruokonen has been going to Elrow since 2011. His first experience was at Row 14. "It's a guaranteed good time," he said. "The amount of effort that goes into the parties makes sure of this. Even if the music is not your cup of tea, you'll still be visually stimulated by the stilt walkers, performers, inflatables, magicians. It's a fully immersive experience and you almost become a part of the show. As much as I love an early morning Ricardo session at fabric, Elrow provides a totally different experience that's equally enjoyable."

Every event is themed—there are 18 themes currently on rotation—and every aspect of the production, from the awe-inspiring sets to the elaborate outfits, is custom-made in-house. (The only exception are the inflatables, which are designed in-house and shipped over by the tonne from China.) Only when you're at one of the events does the full scale of the operation hit you. The attention to detail is extraordinary. At April's Row 14 show, the confetti was green, white and red, the colours associated with the day's theme: the Seville Fair.

The high-point of any Elrow party is the "show," company shorthand for the explosive release of the confetti cannons. These take place four or five times throughout the event. When it's time, all the actors, stilt-walkers and puppeteers converge in the middle of the dance floor, as the music builds to a furious crescendo. When the beat drops, the cannons are triggered. I danced inside a number of these across the Easter bank holiday, first at Row 14 and then at the gargantuan Madrid club Fabrik. Even by the fifth or sixth time, the rush never grew old. It was like being stuck inside a stop-motion film.

My first Elrow was at Ibiza's Vista Club in 2013, and I remember being totally blown away by the experience. It was only the party's second season on the island, so it was still relatively unknown outside of Barcelona. The night was a sensory overload, a whirling kaleidoscope of garish colours, obscene get-ups and non-stop laughter. The vibe was inclusive, infectiously feel-good and, most importantly, totally fresh. I'd never been to an event like it.

I was working for Resident Advisor that night, and my review included this line: "The music, though uninspiring at times, suited the energy of the surrounding chaos." Bouncy tech house with big build-ups and bigger drops has been the soundtrack of Elrow parties since the beginning. Because the music is there to serve a specific purpose—to amplify the action rather than guide the floor—Elrow relies heavily on its residents, a 12-strong team of Spanish DJs who understand the concept. As well as keeping costs down, this approach has allowed domestic artists like Marc Maya, Toni Varga and De La Swing to reach an international audience.

Every Elrow party also features at least one international guest. Scan the flyers and you'll see the same names again and again—Richy Ahmed, Paco Osuna, Patrick Topping. Every now and then De La Serna will splash out on a heavyweight like Carl Cox or Marco Carola, but mostly he works with a rotating cast of artists because, as with the residents, they know what's required of them. It's also important they're on board with the madness.

"I don't want to bring a DJ who doesn't like confetti, doesn't like these things, doesn't like the gimmicks, you know," said De La Serna. "I want to bring a DJ that loves coming to party with us."

Elrow isn't a franchise, so every show is managed in-house. This ensures a consistent and authentic experience, but it entails a lot more work than when a local promoter simply pays a flat fee for the rights to the brand and its affiliated DJs. The way Elrow is currently set up, five events can run simultaneously anywhere in the world, with two technical directors overseeing five teams. In each team is a tour manager and five decorators. Outside of Spain, they use actors and performers from local theatre companies, building a database of trusted entertainers as they go. The bank holiday weekend I spent with De La Serna in April, Elrow had events in Amsterdam, Barcelona, Madrid and Naples.

Working out how to tour the brand without diluting the end product has been the key to Elrow's success. To make sure standards are maintained, either Juanito or De La Serna will attend as many events as possible. "It's important to be at the show because it gives you the real feeling of the party," Juanito told me over coffee in Barcelona. He'd just returned from back-to-back weekends in Shanghai and Ibiza, and you could tell the traveling was taking its toll. "You know obviously people can tell you, 'Hey it was amazing.' But sometimes you have to live it. I have to see how people interact, how they experience it. The mistakes as well, it's important to see your own mistakes and how to do it better the next time."

Juanito was talking about minor blunders—broken props, weak DJ sets, logistical miscalculations—but there have been errors of judgement with more serious consequences. In the run-up to NYE of 2017, Elrow was widely criticised by members of Manchester's Hindu community after a poster surfaced depicting the deity Lord Shiva drinking champagne and holding an iPhone. The poster was promoting two Bollywood-themed events at Albert Hall.

Both Elrow and The Warehouse Project, who co-promoted the events, apologised and the poster was changed. When I asked Satguru about it, he told me that the hectic Christmas period meant the artwork wasn't proofed properly.

Elrow sometimes treads a fine line between fancy dress and cultural appropriation. In some instances, this extends to racial stereotyping and mockery of the poor. At a daylong event at London's Tobacco Dock in March, I saw an actor impersonating a homeless man. In June, during a tour of the Barcelona warehouse, I was shown the costume of a "pimp chicken" character whose feathers were black. (The other chickens were yellow.)

"While globalising a brand can be rewarding in so many ways, we have learnt that we must be aware to keep control of how we have fun and interpret other traditions," the Elrow team told me. "On a couple of occasions, things have backfired, which we've apologised for and worked quickly to make sure the situation is rectified. We never ever set out to cause anyone offence."

Juanito's professional meticulousness was passed down from his father, Juan Arnau Durán (AKA Juan Sr.), who in turn learnt it from his father, Juan Arnau Ibarz. (Tradition runs deep in the Arnau family—all the men, going back four generations, are called Juan; in June, Juanito's wife gave birth to their first child, a boy, named Juan Arnau Rios.) Known fondly as "el abuelo del techno," or "the techno grandfather," Ibarz introduced the family to the nightlife industry back in the '70s, opening what was then one of Spain's largest discotheques. He was famous for being the last one to leave the dance floor at the end of every night, even long after he'd retired. Only a month before he passed away, in 2012, he was in Ibiza doing a recce of the various super clubs.

"That should give you a sense for how much he loved the industry," Juan Sr., now in his '60s, told me in Barcelona. Bald and with large eyes that light up with excitement, he's the most charismatic member of the clan. "Because that was his life. His passion was watching how people enjoyed themselves, how they danced, more than for music itself."

Without the groundwork laid by Ibarz there would be no Elrow. But Ibarz, and his venue, Florida Fraga, make up only half of the story. You can trace the family's roots in entertainment back to 1870, when a young, rebellious entrepreneur named Jose Satorres opened Café Josepet in Fraga, a small farming town of roughly 5,000 people in the northwestern state of Aragon. (All the current crop of Arnau's are from Fraga.) It was a small hangout that became popular with gamblers and local businessmen, and people would travel from miles around to play cards at its white marble tables.

When Satorres died, Café Josepet became Bar Victoria under the guidance of a non-blood relative named Antonio Durán, who transformed the venue from a social club and casino into a cinema. He screened silent movies from the US, soundtracked by amateur local pianists. Business was so good he built a sister venue in the open air.

Ibarz was born in 1927, in the tiny Catalonian village of Aitona. Shortly after, his father, Juan Arnau Cabasés, moved the family to Fraga to expand his flour and olive oil businesses. Realising how lucrative running a cinema could be, Cabasés bought a building for 35,000 pesetas down the road from Cinema Victoria and, in 1943, opened Cinema Florida. (The name was a spin-off from Cinema California, a friend's establishment in a nearby town.)

Florida, which fit 1,300 people, was a hit. With the profits, Cabasés built a new open-air venue, Terraza Jardín Florida, next door; cinemagoers were given discounted entry. This was the family's first move into musical entertainment. At first, groups of local musicians would perform every Sunday, but soon Cabasés was inviting the best national and international orchestras around. Special matinee sessions would begin at midday, just as everyone was leaving church.

The two cinema owners, Durán and Cabasés, were bitter rivals for a while, until, in a Shakespearian twist, their children fell in love. Ibarz and Pilar Durán (Juan Sr.'s parents) married in 1951, uniting Fraga's two feuding families. The wedding party took place in Cabasés' third and newest venue, Salón Florida, a covered space with a large disco ball built to host dances in winter. On the same spot today sits Florida 135, the latest incarnation of the decades-old venue.

Part of the reason the Arnau men have left such a mark on their respective nightlife industries is they understand the value of surprise, a lesson that has been passed down from generation to generation. Perhaps the earliest examples of this were the performances of Cuban singer Antonio Machín in the '50s. He sung boleros, a slow style of Latin music with romantic lyrics, that encouraged men and women to dance pressed together, rather than separately or with one hand on each other's hip. For a small community like Fraga, this was transgressive stuff.

Cabasés died in '62, leaving the family business to Ibarz and his brother, José. In 1973, the two sons, with help from Spanish architect Javier Regás, opened Florida Fraga, the family's first discotheque. Regás, foreseeing a change in the way music would be performed, put the booth in the middle of the dance floor. Two years later, the building burnt down, but within a couple of months it was back open, identical except for the colour of the walls.

Juan Sr. began working alongside his father in 1978, aged 22. The following few years were some of the most challenging in the family's history. Several new state-of-the-art venues sprung up in nearby towns like Lleida, Monzón and Binéfar, leaving Florida struggling for numbers. This coincided with the family's other business ventures, in animal foodstuffs, going bankrupt.

"The banks and the creditors took everything," Juan Sr. told me in a shabby office at Row14. It was several hours into the party and the walls were vibrating violently. "All we were left with was Florida. Everything that's happened since then came from that moment."

Juan Sr. tracked down Regás (the architect) and, together with Ibarz, the three began brainstorming ideas for how to improve Florida Fraga. The finished product, Florida 135, was—and still is—unlike any other club in the world. Cavernous and multi-levelled, its interior was inspired by Blade Runner and modelled on a real street in The Bronx, complete with lamp posts, shopfronts and neon signs. "He [Ibarz] wanted a unique venue where the crowd felt like they were walking into an open space rather than a closed one," Juan Sr. told the journalist Lucía Aresté in 2014. Another music writer described it as the "super club where it's impossible to be bored."

By the time Florida 135 opened, in 1985, Ibarz had taken a backseat. Juan Sr., now in charge, quickly realised that in order to compete the club had to offer something more than just the latest pop hits. He tried various things but nothing stuck. He needed a fresh sound with a longer shelf-life.

Around '87 or '88, Juan Sr. and his wife, Mari Cruz Lasierra, took an expedition around Europe in search of inspiration. They went to Tresor in Berlin and illegal raves in the UK and the south of France, listening to DJs like Carl Cox, Jeff Mills and Sven Väth playing techno and acid house. As much as the music, it was the culture surrounding these events that left a deep impression—the flyers, the clothes. When they returned to Fraga, Juan Sr. tried to explain to Ibarz what they'd seen but he couldn't find the words. "That's the best sign!" Ibarz told his son, who relayed the story at this year's IMS conference in Ibiza. "You have to bring it here."

Francesco Farfa, Laurent Garnier and Richie Hawtin all played Florida 135 for the first time in 1994. At first, their music received a lukewarm response—punters were used to hearing bakalao and mákina, two popular local sub-genres of techno that rarely dipped below 135 BPM. On Garnier's debut, the crowd dropped from 3,000 to 1,000 by the end of the night. Farfa, who Juan Sr. had spotted at a festival in Toulouse, has similar memories of his first set. "For 20 minutes, people remained motionless as if they were looking at an alien," he told me over email.

"If you try something new or experimental and everyone dances, that usually means it's not actually that new," said Juan Sr. "If something works first time, it's unlikely to be a fresh idea. You need to surprise people, there needs to be a period of education."

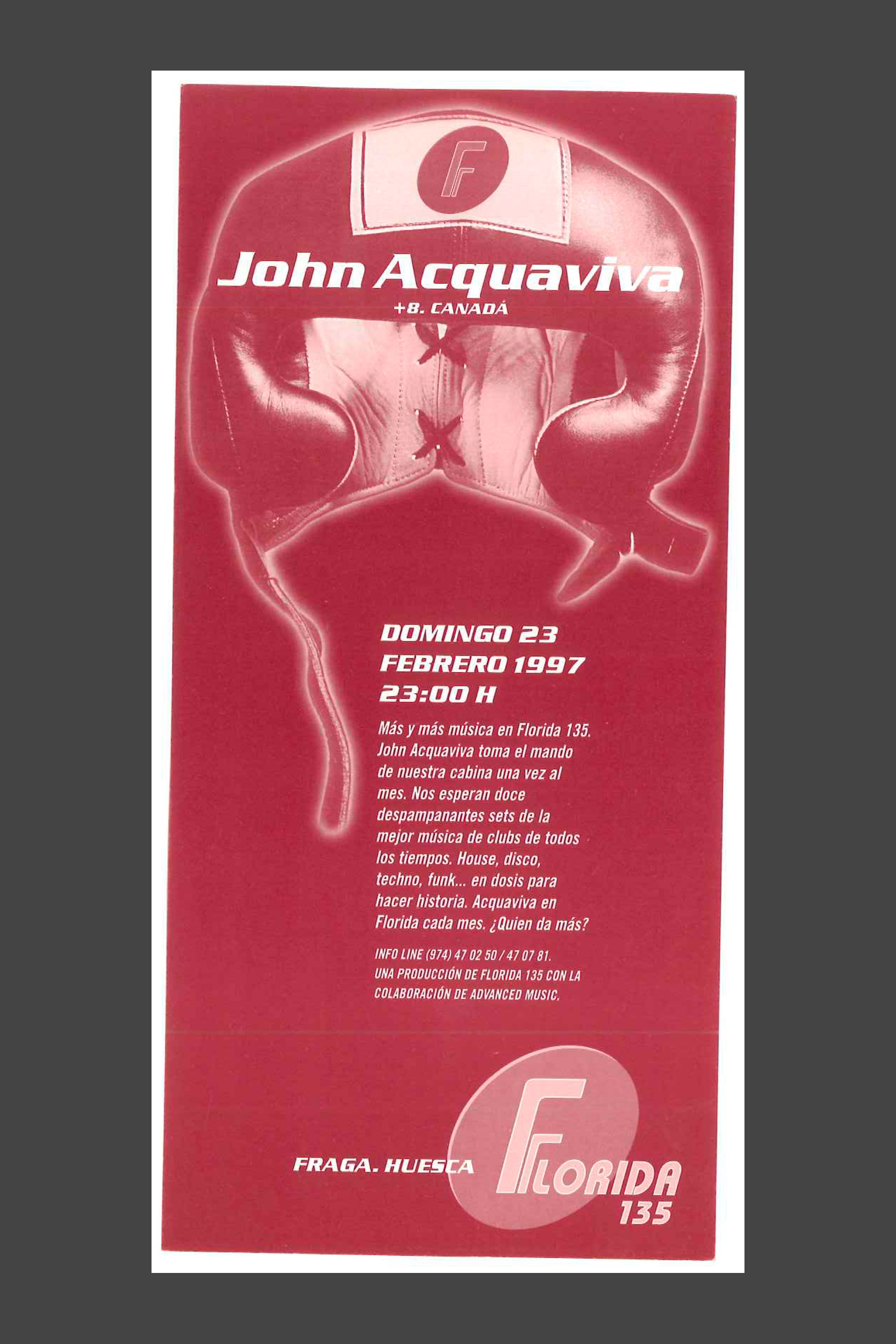

After several years of losing money, house and techno eventually caught hold in Florida 135, around '97 or '98. Today, the walls of the club's offices are covered in photos of Ibarz and Juan Sr. with their arms around various fresh-faced luminaries of the day: Derrick May, Marco Carola, Surgeon. It became known as "La Catedral Del Techno," and people would drive from all over Spain to party at one of its extended sessions. (It helped that Aragon's afterhours laws were lax compared to nearby Catalonia.) "For a decade it was the focal point of Spain and the international techno world," John Acquaviva, a regular at the club in the '90s, told me over email.

It was around the late '90s that Juanito and Cruz, the current directors of Elrow, entered the frame. As teenagers, they would spend most weekends partying in Florida 135. Every year, at Juan Sr.'s blossoming desert rave, Monegros Festival, they'd watch as their father dealt with the biggest artists in the world. It seemed logical that one day they'd take over the family business, but their parents weren't so keen.

"They didn't want to see myself or my sister going to the nightclub every single weekend and being there with drugs, alcohol, surrounded by the same people over and over and over," said Juanito. "They tried to push us out because they thought it could never be a good thing for us."

Juanito, who's older than Cruz by two years, went to university in Barcelona and then in San Francisco, before spending time in Sydney and Cape Town. He loved South Africa, so he decided to stay on for an extra year, but this was cut short by a phone call from his father, who waxed lyrical about a new location he'd found near the airport in Barcelona. "This is when he told me, 'Juanito I have got a club, let's build it and you're going to start running it,'" he said. "Then I flew back and I started. I remember it was like six people—the booker, the secretary, myself, my dad and my sister, who had also just come back."

Row 14 opened in April 2008, but within a year business was so bad that the family considered closing it. "It didn't work," said Juanito. "We thought we could do the same as Florida but we realised that the industry was saturated. Everyone was doing the same music, the same DJs, the only way to fight was by paying more money. Florida is a special space with a lot of history, but Row 14 didn't have history. When we were about to close it down I told my father: 'Listen, if we are going to create something different in the mornings, we have to start from zero. Forget about DJs, forget about everything else, forget about the past. We have to create a full new experience."

Juanito, Cruz and some of their closest friends gathered around a table and began brainstorming ideas. "We were bored of the same things everywhere, and so among our friends we started to ask ourselves, 'What's missing?'" said Cruz. "It was this idea of how to dress, what tattoos to have... It was boring to try and replicate this, we wanted something more crazy."

"The electronic market was the same for too many years," said Juanito. "For many years it was only about the music. There was no experience, there was nothing personal. When my father and grandfather started Florida 135 they wanted to create a really special club, something unique in the world. When we did Elrow, I told my father the same: if we do something in Barcelona, we have to try and change the mentality of the people and try to make it more about them. So when they come to the show we have to make them happy, and they must be the show."

This emphasis on the customer experience over the music is what connects the work of the last three generations of the family. Juan Sr. admitted to me that it was the theatre of promotion, rather than music itself, that interested him. Ibarz was more into music—the British drum & bass DJ Fabio would apparently send him tracks—but it was a lifelong fascination with observing how people behaved on the dance floor that drove him. Juanito and Cruz grew up with music and are clearly passionate about it. But in Elrow, they created a party where the music is secondary. The punter, not the DJ, is the protagonist.

Elrow launched on Sunday, June 20th, 2010. It began as a weekly semi-legal afterparty, taking advantage of a loophole in the law that meant they could open at 7 or 8 AM. After a couple of years, the council stopped turning a blind eye and the parties switched to the afternoons, starting at 4 or 5 PM and running until Monday morning.

Before every party, Juanito would go to Chinatown and spend €300 on toys, stickers and masks, which he and Cruz would then hand out on the dance floor. One particularly hot summer's day, the shop was stacked with inflatables, so he bought a few and gave them out. Later, they started throwing the inflatables from the roof. Handheld confetti canons became confetti machines. They introduced stilt-walkers. They hosted their first themed party, Row Show, and decorated the entire club. Slowly, the concept evolved.

In 2012, Elrow set out to conquer Ibiza. A contact at Privilege offered them the club's smaller second room, then called Coco Loco. Part of the deal was they could rename the space and redecorate it. They settled on Vista Club, inspired by the beautiful views of nearby San Rafael from the dance floor. Budgets were small, so the team ran their workshop out of a rented flat in Ibiza Town. For any larger design pieces, the dance floor became a makeshift studio.

Elrow took over Saturdays at Vista Club across 2012 and 2013, before upscaling to Space, partnering first with Kehakuma, in 2014, and then going it alone. It quickly became one of the iconic club's most popular residencies—some weeks were even busier than Carl Cox's Music Is Revolution party, the island's biggest house and techno night at the time. After Space closed in 2016, Elrow upscaled again and moved to Amnesia, where it's just completed another record-breaking season.

"The turning point really was Ibiza. You do it every week, but every week is different people because people don't stay for the whole season," said De La Serna. "Every weekend it was like English people, Dutch people. They saw it and loved it, and that's when we started to get calls from outside of Spain to start doing things."

Rag Satguru's first Elrow experience was at Vista Club in 2012. "We're at this party, the music's alright, and then suddenly out of nowhere, things start appearing. A clown comes climbing across in the front of the decks with a tie that's sticking up. Unicorns are flying from the ceiling. At one point, even the security guard has a backpack on, and a C02 gun, and everything goes 'phwoar.' I'm like, 'Oh my god, this is insane.'"

Satguru, who co-runs the house and techno management company Grade, started booking in some of his acts—Seth Troxler, Eats Everything—for shows. In June of 2014, he was at an Elrow party in Barcelona with Jo Vidler, the creative brain behind UK festivals Secret Garden Party and Wilderness. "She was like, 'Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god. We have to do this. We have to bring this in.'" Vidler pitched Juanito, who agreed, and on March 7th, 2015, Elrow landed at London's Village Underground.

"Surprise International Guest DJ" reads the top slot on the RA event page. Leaving headliners unannounced quickly became a trademark of Elrow parties in the UK, a canny strategy that drummed up intrigue and allowed Satguru and De La Serna, who joined the company in 2014, to book big acts at lower fees. This meant more money could be spent on the important things: production, decoration, confetti.

"People in England didn't know what Elrow was, so they weren't gonna want to pay £50 it," said Satguru. "That made it tricky. I needed to sell it for like £10, £15, £20. So I thought, let's not take anything away from the Elrow brand by putting any headline DJs on it. Let's just say no DJs or surprise guest and do it this way. I set up the date, it was a daytime party, and I knew some DJs—now key Elrow DJs—who could go and play somewhere else at night. It was a way to get good DJ talent while keeping the ticket price lower."

Satguru began touring Elrow all over the UK, introducing it to cities like Newcastle, Southampton and Birmingham. Festival stages popped up at Lovebox and Parklife. Meanwhile, in London, it developed close relationships with Studio 338 and, later, London Warehouse Events. One of the brand's greatest triumphs came in November of 2016, when they were asked by the Victoria And Albert Museum to host the turning on of the Christmas lights in London's Carnaby Street. So many people turned up—between 30 and 40,000—that the police shut it down an hour earlier than planned.

Around this time, events in the UK started selling out in record time. For a show at Manchester's Warehouse Project in October of 2016, 2,000 tickets went in five minutes. Two months later, at Motion in Bristol, Elrow shifted double that in 15 minutes. In 2017, they put 6,500 tickets up for an all-dayer at Tobacco Dock in London—arguably dance music's most competitive market—and sold out in an hour. At the time that was their biggest UK show, but shortly after they announced Elrow Town London, a takeover of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park scheduled for August. When 15,000 tickets went on sale in June, they went in just four hours. The lineup was still TBA.

I asked Will Harold, one of three directors at LWE, Elrow's current partner in London, why he thought the party was such a success. "I think it's been a breath of fresh air. It's reminded us all that there are lots of ways of going out and letting loose on the dance floor. It doesn't always have to be serious and about DJs. It can just be about coming together having an amazing time and being transported off into a totally different world. That's what Elrow do so well… They manage to transport you off into a totally different dimension."

Given how popular it's proven in Europe and the UK—dance music's most challenging markets—it's easy to envision another run of record-breaking years for Elrow. In the short term, the Superstruct-backed expansion will help the brand settle into dozens of new territories. The thousands of clubs and festivals across South America, North America, Australia, South Africa, Russia and Asia represent a staggering wealth of opportunities.

Beyond that, the challenge will be to keep the concept fresh while retaining the party's original, fun-loving spirit. "If you are able to understand what young people want, and you are willing to go the extra mile, you can continue developing and changing in line with people's tastes," said Cruz. "I assume that in a few years what young people want will have changed, but if you know how to spot this and listen to them, then you can adapt accordingly. Just as my family always has done."